Blogs

Imagine holding out your hand and catching words, pictures, and information passing by. That's more or less what an antenna (sometimes called an aerial) does: it's the metal rod or dish that catches radio waves and turns them into electrical signals feeding into something like a radio or television or a telephone system. Antennas like this are sometimes called receivers. A transmitter is a different kind of antenna that does the opposite job to a receiver: it turns electrical signals into radio waves so they can travel sometimes thousands of kilometers around the Earth or even into space and back. Antennas and transmitters are the key to virtually all forms of modern telecommunication. Let's take a closer look at what they are and how they work!

How antennas work

Suppose you're the boss of a radio station and you want to transmit your programs to the wider world. How do you go about it? You use microphones to capture the sounds of people's voices and turn them into electrical energy. You take that electricity and, loosely speaking, make it flow along a tall metal antenna (boosting it in power many times so it will travel just as far as you need into the world). As the electrons (tiny particles inside atoms) in the electric current wiggle back and forth along the antenna, they create invisible electromagnetic radiation in the form of radio waves. These waves travel out at the speed of light, taking your radio program with them. What happens when I turn on my radio in my home a few miles away? The radio waves you sent flow through the metal antenna and cause electrons to wiggle back and forth. That generates an electric current—a signal that the electronic components inside my radio turn back into sound I can hear.

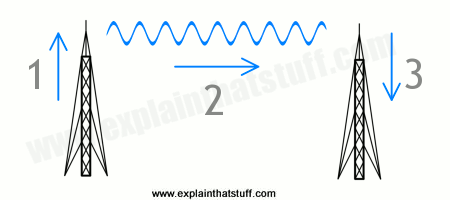

How a transmitter sends radio waves to a receiver. 1) Electricity flowing into the transmitter antenna makes electrons vibrate up and down it, producing radio waves. 2) The radio waves travel through the air at the speed of light. 3) When the waves arrive at the receiver antenna, they make electrons vibrate inside it. This produces an electric current that recreates the original signal.

Transmitter and receiver antennas are often very similar in design. For example, if you're using something like a satellite phone that can send and receive a video-telephone call to any other place on Earth using space satellites, the signals you transmit and receive all pass through a single satellite dish—a special kind of antenna shaped like a bowl (and technically known as a parabolic reflector, because the dish curves in the shape of a graph called a parabola). Often, though, transmitters and receivers look very different. TV or radio broadcasting antennas are huge masts sometimes stretching hundreds of meters/feet into the air, because they have to send powerful signals over long distances. But you don't need anything that big on your TV or radio at home: a much smaller antenna will do the job fine.

Waves don't always zap through the air from transmitter to receiver. Depending on what kinds (frequencies) of waves we want to send, how far we want to send them, and when we want to do it, there are actually three different ways in which the waves can travel:

Artwork: How a wave travels from a transmitter to a receiver: 1) By line of sight; 2) By ground wave; 3) Via the ionosphere.

- As we've already seen, they can shoot by what's called "line of sight", in a straight line—just like a beam of light. In old-fashioned long-distance telephone networks, microwaves were used to carry calls this way between very high communications towers.

- They can speed round the Earth's curvature in what's known as a ground wave. AM (medium-wave) radio tends to travel this way for short-to-moderate distances. This explains why we can hear radio signals beyond the horizon (when the transmitter and receiver are not within sight of each other).

- They can shoot up to the sky, bounce off the ionosphere (an electrically charged part of Earth's upper atmosphere), and come back down to the ground again. This effect works best at night, which explains why distant (foreign) AM radio stations are much easier to pick up in the evenings. During the daytime, waves shooting off to the sky are absorbed by lower layers of the ionosphere. At night, that doesn't happen. Instead, higher layers of the ionosphere catch the radio waves and fling them back to Earth—giving us a very effective "sky mirror" that can help to carry radio waves over very long distances.

How long does an antenna have to be?

Photo: This telescopic FM radio antenna pulls out to a length of about 1–2m (3–6ft or so), which is roughly half the length of the radio waves it's trying to capture.

The simplest antenna is a single piece of metal wire attached to a radio. The first radio I ever built, when I was 11 or 12, was a crystal set with a long loop of copper wire acting as the antenna. I ran the antenna right the way around my bedroom ceiling, so it must have been about 20–30 meters (60–100 ft) long in all!

Photo: Antennas that use line-of-sight communication need to be mounted on high towers, like this. You can see the thin dipoles of the antenna sticking out of the top, but most of what you see here is just the tower that holds the antenna high in the air. Photo by Pierre-Etienne Courtejoie courtesy of US Army.

Most modern transistor radios have at least two antennas. One of them is a long, shiny telescopic rod that pulls out from the case and swivels around for picking up FM (frequency modulation) signals. The other is an antenna inside the case, usually fixed to the main circuit board, and it picks up AM (amplitude modulation) signals. (If you're not sure about the difference between FM and AM, refer to our radio article.)

Why do you need two antennas in a radio? The signals on these different wave bands are carried by radio waves of different frequency and wavelength. Typical AM radio signals have a frequency of 1000 kHz (kilohertz), while typical FM signals are about 100 MHz (megahertz)—so they vibrate about a hundred times faster. Since all radio waves travel at the same speed (the speed of light, which is 300,000 km/s or 186,000 miles per second), AM signals have wavelengths about a hundred times bigger than FM signals. You need two antennas because a single antenna can't pick up such a hugely different range of wavelengths. It's the wavelength (or frequency, if you prefer) of the radio waves you're trying to detect that determines the length of the antenna you need to use. Broadly speaking, the length of the antenna has to be about half the wavelength of the radio waves you're trying to receive (it's also possible to make antennas that are a quarter of the wavelength, though we won't go into that here).